Seated in a chair a few feet away, you still have to strain to hear Nadav Goshen speak. He’s quiet, but thoughtful. And, from the looks of it, slightly nervous. It’s clear that the serial executive isn’t used to the spotlight as he sits down for his first interview since being appointed the CEO of one-time 3D printing savior MakerBot back in January.

Goshen has a small stack of papers sitting on a table beside him, should he need to consult any notes. He never actually looks over, however. After months of behind the scenes meetings, he’s got the company’s new line down, pat. His voice rarely raises above a whisper during our conversation, but he speaks thoughtfully and pragmatically. He speaks of a company that’s humbled. One that has learned from its mistakes.

After a few minutes, it’s impossible to miss the stark contrast with Bre Pettis, the mutton-chopped, co-founder whose bespectacled face became as synonymous with the company as any mascot or logo. He was a one-man manifestation of the MakerBot spirit, and by extension the desktop 3D printer revolution.

He held a Replicator printer aloft on the October 2012 cover of Wired, flanked by the bright orange words “This Machine Will Change the World.” He yucked it up with Stephen Colbert on Comedy Central, before sending a 3D printed bust of the blustery faux right wing talk show host into space. It was all very 2011.

MakerBot opened up storefronts in strategic locations across the country, announced ambitious plans to begin manufacturing 3D printers in the US and opened up a sprawling office space high up in a downtown Brooklyn office space overlooking a huge swath of lower Manhattan. The stores were quietly shuttered and manufacturing moved to Shenzhen, “where things should be manufactured,” one employee off-handedly remarks.

The office remains. And we’ve lucked out, having chosen what feels like the first real day of spring in New York City. The view is stunning with the sun streaming through the lower Manhattan skyscrapers, and Goshan is quietly chipper for a man who three months before was tasked with what must feel like the weight of the 3D printing world. He brushes off the suggestion that he inherited a difficult position. “No,” he answers softly, but defiantly. “MakerBot is in a great state.”

Goshen highlights the moves the company has made over the last several months. In September of last year, then-CEO Jonathan Jaglom unveiled the Replicator+ and Replicator Mini+. But the new printers were only a piece of the conversation, pointing to a larger cultural shift for the company, a move away from attempting to predict or control the conversation.

“We were under the assumption of trying to aim for growth patterns,” says Goshen. “Trying to aim for a specific time and place where everything will meet and I think this trying to pinpoint a point in time and space is not healthy. Much more healthy is to look at customer needs, grow with the market.”

Build platform

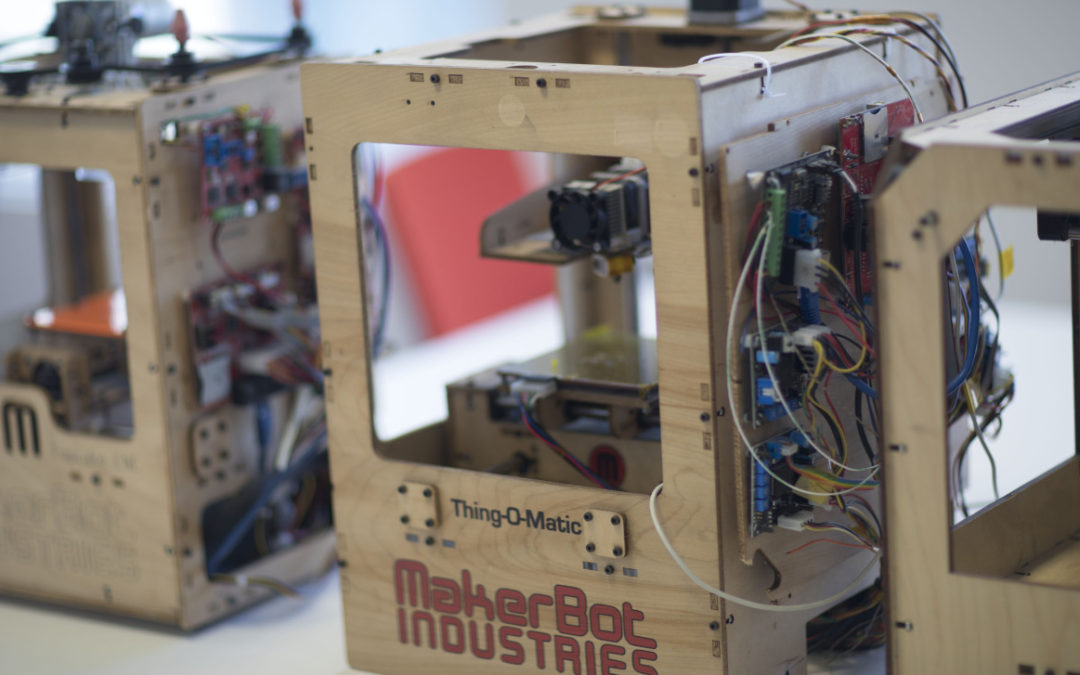

MakerBot’s humble beginnings were precisely what made the company the perfect poster child for the desktop 3D printing movement. The team was an off-shoot of sorts from RepRap, a project founded in 2005 by University of Bath professor Adrian Bowyer, with the goal of creating a self-replicating machine – or at the very least, one that could build a majority of its own parts.

In 2007, Pettis and fellow makers Zach Smith and Adam Mayer holed up in New York City makerspace NYC Resistor and set out to build their own machine based on RepRap’s open-source schematics, fueled by, the way Pettis tells it, ramen, caffeine and a $25,000 laser cutter members of the space had chipped in to buy. Bowyer was an early-stage backer, helping to fund the creation of the company’s earliest kit.

More than one press outlet noted the parallels between it and early Silicon Valley success stories like Apple, and Pettis seemingly, was happy to fill the role of Steve Jobs. A former middle school art teacher and employee of Jim Henson’s Creature Shop, he spoke with the unabashed confidence of a man ready to change the world.

“We’re out to fuel the next industrial revolution,” Pettis told the crew of Print The Legend, a Netflix documentary that charted the beginnings of MakerBot and desktop 3D printing, “by putting the power to manufacture things in your hands.” That statement wasn’t an outlier.

It seems like a million years ago now, but the sentiment is indicative of an overall feeling in the tech community toward 3D printing. We were in the midst of a third industrial revolution. 3D printing was about to change everything, and MakerBot was smack dab in the eye of that storm.

Believing the hype

Over the next couple of years, MakerBot’s growth was downright explosive. The company expanded its staff from 40 employees to around 600-plus by its own account. It added several new printer configurations to its line, along with a turntable-style 3D scanner and an online store, aimed at selling premium prints alongside the company’s longtime free Thingiverse database. The unveilings took on the air of small scale Apple keynotes, complete with new products hidden beneath black cloths.

In 2013, industrial 3D printing heavy weight Stratasys purchased MakerBot at the height of its powers and hype cycle for $403 million. It was a healthy sum for a company that, less than half a decade before, was selling wooden kits built in a local makerspace. In 2015, Pettis left the company he’d helped found, taking his Bold Machines workshop with him.

Pettis and Stratasys both declined to be interviewed for the piece, though the latter offered up comment from CEO Ilan Levin,

In addition to Stratasys’ commitment to the ongoing development of the professional rapid prototyping segment, we believe that there is strategic value in capturing entry-level users within the desktop segment where we can provide differentiated value.

We remain confident in the long-term opportunity in the desktop segment, and will continue to invest in products that serve the entry-level professional and education markets. We believe MakerBot maintains the leading desktop brand, with the most developed software ecosystem within the industry.

To many, 2015 felt like the beginning of the end for MakerBot – and, perhaps, desktop 3D printing as a whole. The company underwent a massive contraction shuttering its flagship store and laying off 100 employees, a massive chunk of the company’s overall staff. Citing expenses and the industry “volatility,” MakerBot closed down its massive 175,000 square foot Brooklyn manufacturing facility less than a year after its much ballyhooed grand opening.

3D printing’s promise of hyperlocalized manufacturing and a third industrial revolution would have to take a backseat to the affordability of Chinese labor. And the fallout hasn’t stopped. This February, the company announced that it would be laying off one-third of its staff, leaving the current number at around 100. Things have proven equally volatile up top. Goshen is the third person to fill out the CEO role since Pettis’s exit.

With four years under his belt, Engineering VP Dave Veisz is a downright veteran. “It feels like I’ve been in this role for five years or so,” he says with a laugh about the 13 months he’s spent in his current position. “With the hype on the way up, too, there was always constant change,” he adds. “The people that have been here for three to five years are used to almost like a new company every six months, every year.”

Shifting gears

Goshen hardly mentions the consumer space during our conversation, unless prompted to do so. Like the executive himself, the company is dramatically different from the one that graced the covers of mainstream tech publications half a decade ago. Changing the world is a bit further down the list of the company’s goals.

“I don’t think that right now there is a consumer 3D printing successful product offering,” Goshen admits. The company’s current strengths are primarily in education — making potential professional users comfortable with 3D printing techniques. “This is not exactly 3D printing…