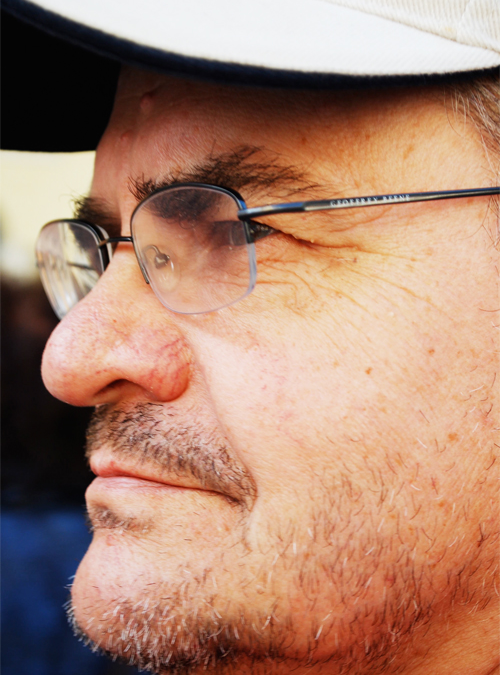

Welcome back to Inside the Mind of a NYC Angel Investor, a new series at AlleyWatch in which we speak with New York City-based Angel Investors. In the hot seat this time is John Ason, who has been investing in startups for over 20 years and serves as a mentor at Astia, Springboard, 37 Angels, The Vinetta Project, ERA, DreamIt, and TechLaunch. John spent the early part of his career at AT&T Bell Laboratories and today sees over 4,000 pitches per year as a professional angel investor. John sat down with AlleyWatch to talk about managing risk as an angel investor, the types of angels that make the biggest mistakes, and his belief that industry experience is overrated.

If you are a NYC-based Angel interested in participating in this series, please send us an email. We’d love to chat. If you are interested in sponsoring this series that showcases the leading minds in angel investing in NYC, we’d also love to chat. Send us a note.

Bart Clareman, AlleyWatch: Tell us about your journey into investing in startup ventures?

John Ason: I spent a career at Bell Laboratories with AT&T always doing technology work. During the last 15 years I was doing marketing and selling of large software systems to telecommunications companies overseas, primarily the Far East.

I made money in the public markets, and retired for about a year. I goofed off, played around, and got bored, so I then got into angel investing.

It was not a cultural shock in any way because I was doing bleeding edge technology at Bell Laboratories, so everything was the same other than that startups had no shipping department or legal department so you had to do everything.

Bell Labs is talked about as one of the forefathers to the New York tech scene – what was it like to work there, and why was it so foundational to the development of the entrepreneurial ecosystem here?

At Bell Labs if you wanted to you could do bleeding edge work. You could always get work that was very different, very new. That was one big impetus.

Second, the research group had some of the sharpest, smartest people around. A lot of friends of mine were from the deep research area.

We also experienced the transition from being a purely US company to an international company, and I grew as part of that transition, I did a good 15 years internationally, primarily Japan and the Far East.

Also I had the opportunity to do a lot of projects like the AT&T Internet, the AT&T Cloud, which were way ahead of its time. The infrastructure, the software, the virtualizations were not available at the time, so these were nonfunctional to a large degree. Nevertheless, it gave me a very good background in those products and a glimpse into the future. Also, I loved having such a variety as opposed to working for a company where you were just programming COBOL or something for 30 years.

On your website you define yourself as an Early Seed State Angel, which you further define as an Angel that “invests in companies that have an idea, 1 or 2 founders, no revenues, no completed product and no history of success.” Why do you prefer early stage to later stage angel investing?

One reason is it’s exciting, and you’re learning new things. The second reason is, my research indicated that the return per dollar invested is highest at the early seed stage, then it drops off, then it comes back to a rational number in the public markets. So I felt I could get the best returns if I could manage the risks. My whole focus was on managing risk.

How do you manage risk with early stage companies, which, as you say, may have little more than a founder or two and an idea?

I don’t overpay for companies. I have a rigid formula that for the complete round the founder has to give up 20-30% equity. 90% of all startups fit into that range anyway, so I made it a rule. Under 20% it’s not interesting, over 30% you almost likely get crammed down in later rounds. This also has the advantage in that it encourages the founder to raise more money, because if they raise more money they’re not diluting themselves, and they’re reducing the risk for the investors. The more money you raise the less risk – because you can fail, you can do other things, you have longer runway.

How much runway do you like a company to have coming out of the Seed round?

I want the funding to last a minimum of 12 months, preferably 18 months.

You mentioned how you have rigid rules around how much equity is given away in a Seed round – that 20-30% range you described. Is it a tension for you balancing that rule with the “fear of missing out” on the next Uber, say, if only you’d been willing to go to 19%?

It’s not hard for me. I’ve been doing this for 20 years. In my first 10 years I would do that, and I had a 90% failure rate, which is pretty standard for what I do. My last 10 years my failure rate is 25-30%. By having a disciplined approach, you tend not to overpay, and overpaying is your main risk factor. I don’t ever value a company, it just has to meet my criteria – that it’s big enough to provide 10x return potential.

What’s your average initial check size?

$100K is what I normally do, though I’ll do a few $50K and over the life I’ll put in $500K.

I’m curious about rules of thumb for the angel world. You often hear in VC that each investment needs to have $1bn-plus potential in order for it to make sense for VC economics. Is there anything similar in angel investing, where each investment you make you have to believe it can become X?

The way I describe it is, each investment needs to have at least a 10x return potential, and you need to make at least 10 investments. If you’re going to do $25K investments you need to have at least a bankroll of $250K; hopefully you have like $500K and you can put $50K into 10 opportunities. Out of that, you should get one that’s worth 10x or greater.

The way the economics work, on ones that are successful you have the opportunity to further invest. Your subsequent dollars are not going to be the big winners but they’re going to add incrementally to your return. It also ensures you maintain an insider’s look into what’s going on, and that’s what matters in this world.

What are the essential rights or protections an angel needs?

The only rights I want one are prevent a recapitalization – I want to have the ability to veto a recapitalization or founders issuing more stock, as well as founders taking excessive salaries. You’ll usually get participation rights for the next round to maintain your positioning.

If the other investors want other special rights like preferences I will not invest. I want as clean vanilla as possible, so when a VC looks at it they say there’s nothing here to analyze, take out or modify.

How often does that happen that you’ll co-invest with other angels and they’ll ask for the kinds of rights and protections that you know will cause problems when VCs enter the picture?

That’s only occurred once in the last 10 years. What occurred is, a founder offered me standard terms and I agreed to them, signed off on it. He had eight other investors that he went to and got their input, they all provided some special things they wanted. When it got back to me six months later, I said, “I won’t invest if that’s in there, so please take all the changes out.” They did, and the company got funded with a standard agreement and they subsequently got another round.

Because I get so much deal flow, when stuff like this tends to happen, I just walk away. I don’t want to waste time negotiating with other investors. The rule is, somebody emerges as the lead investor, and then you follow the lead investor. It’s not a committee approach.

As an entrepreneur you often hear that VCs don’t want a messy cap table. At what point does the number of angel investors become problematic in your experience? How many is too many?

I’ve never had that as a problem as long as it’s clean; that is, it doesn’t have too many classes. Sometimes the VC will say, “we’ll convert everybody at this formula in this round to clean it up.” It’s the special terms; somebody may have a consulting agreement or an extra preference, it’s those things that have to be cleaned up and in many cases, those people have some sort of veto right.

One company, in which I invested had some of these special terms, so what the VC said was, “I want 100% agreement and it has to reach my desk by noon Friday or I’m walking away from it.” It was a friendly thing, but it was, “hey guys, we’re not going to be playing games.”

Back to the website – you further describe yourself as a “Renaissance Angel,” which you define as “intellectuals who pursue Angel investing for knowledge and satisfying experiences. Their portfolios are very diverse and eclectic having no discernible patterns. Financial returns are of secondary importance.” Start at the top – what are the bits of knowledge and satisfying experiences you gain out of angel investing?

I learn about different industries, different business models, different people, different cultures – it’s a constant learning progress, which is very satisfying to me.

I especially like young people who challenge the existing norms and are successful.

Talk about the “no discernible patterns” bit. There has to be some pattern, no? Something you routinely look for?

No.

Then what do you look…